View exhibition catalogue

1. Walking

Suburban streets are not designed for walkers. The pavements are irregular or uneven—a concrete track turns into a thin nature strip, and the walker must decide whether to continue along the band of grass or move to the edge of the road. A solitary walker garners attention because walking along a suburban street in the middle of the day, or the late afternoon, seems like a suspicious thing to do. Why walk when you can drive? Why walk along a back street instead of the main drag? Why walk on your own? This kind of walker is particularly suspicious because this walker seems to meander and to take slow hesitant steps. This walker looks lost, but not quite, and bends down to inspect the grass. This walker appears to be carrying junk.

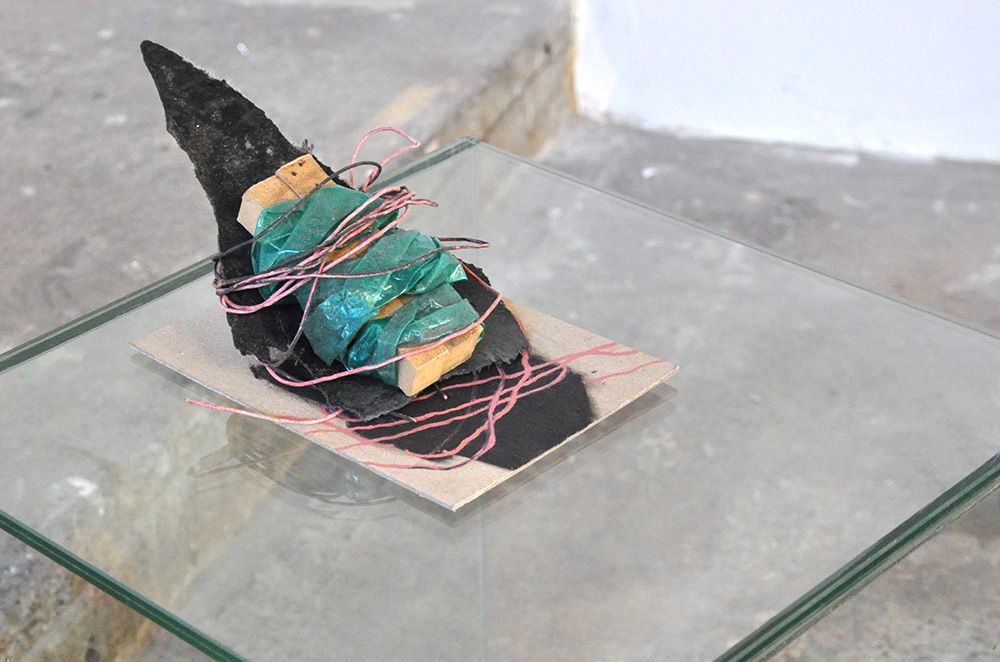

For her solo exhibition Lifted, Rebecca Gallo has undertaken a series of walks using the location of Peacock Gallery and the Auburn Botanic Gardens as her starting point. She has walked and re-walked routes along Chisholm Road, Elm Road, Carnegie Street and Edgar Street; she has passed the Joy of Life Christian Church and the Auburn Tennis and Recreation Club, tracked the route of the Duck River, the outline of the Webbs Avenue Playing Fields, and the perimeter of the council depot. During each of these walks Gallo has found, and picked up, various items that have caught her attention (a set of broken keys, a shuttlecock, a button)—items that have been discarded, lost, left as refuse, or buried.

Suburbia exists in our imaginary as the quarter acre block, the hills hoist and the red brick house; as the site of middle-class aspiration and consumerism; as the settler nation’s thumb print (never-ending sprawl working to cover up and occupy land that was never ceded). In Blue Velvet (1986), David Lynch places a severed ear next to a rose bush and a picket fence, forever associating the white picket fence of suburbia with concealed horror and decay. It is also the place where most of us live and call home.

But Gallo is not placing objects down, she is picking them up. It is an action that is less about exposing the seamy underbelly of a suburb (how terracotta tiles and manicured lawns repress our desires) and more about attention and care to the particularities of place. In searching for materials that have been deliberately dropped or misplaced, Gallo must focus her eyes downward—zooming in on the cracks in the pavements, the edges of the gutters, or the blades of glass. She is performing the act of gleaning: finding value in what appears, on the surface, to have no worth.

2. Balancing

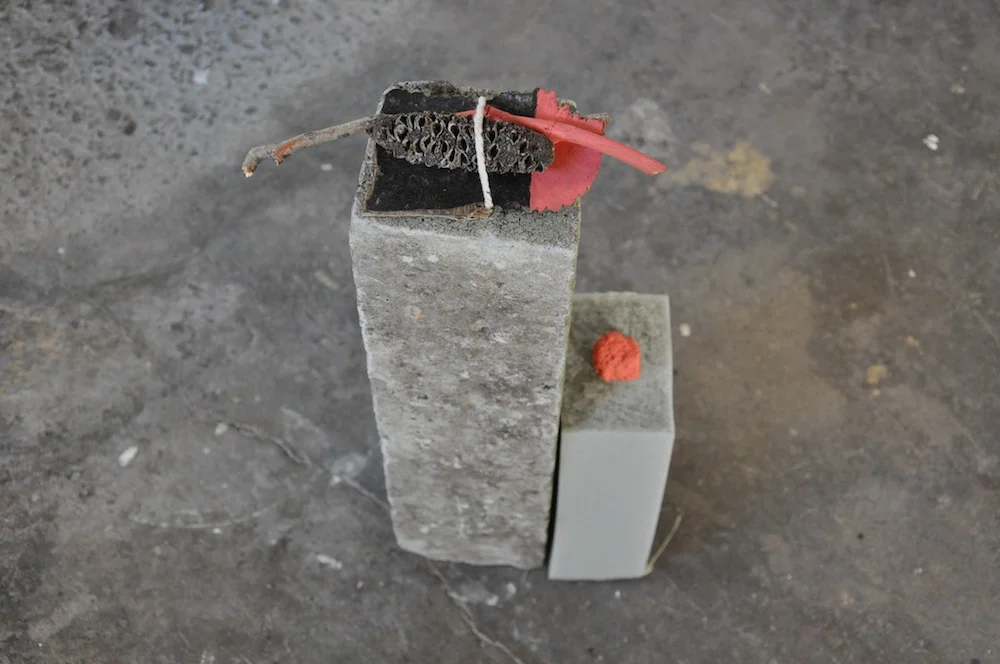

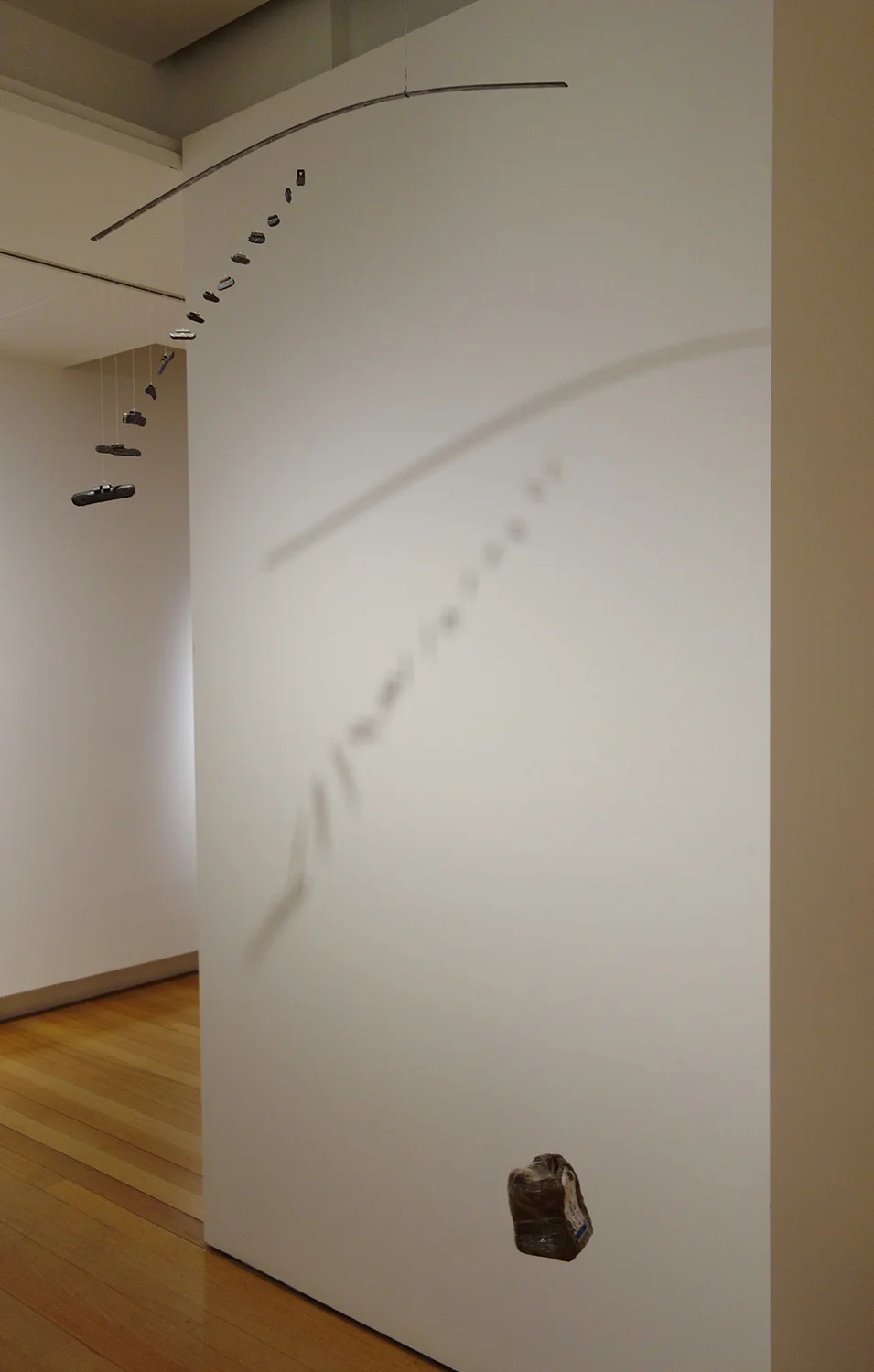

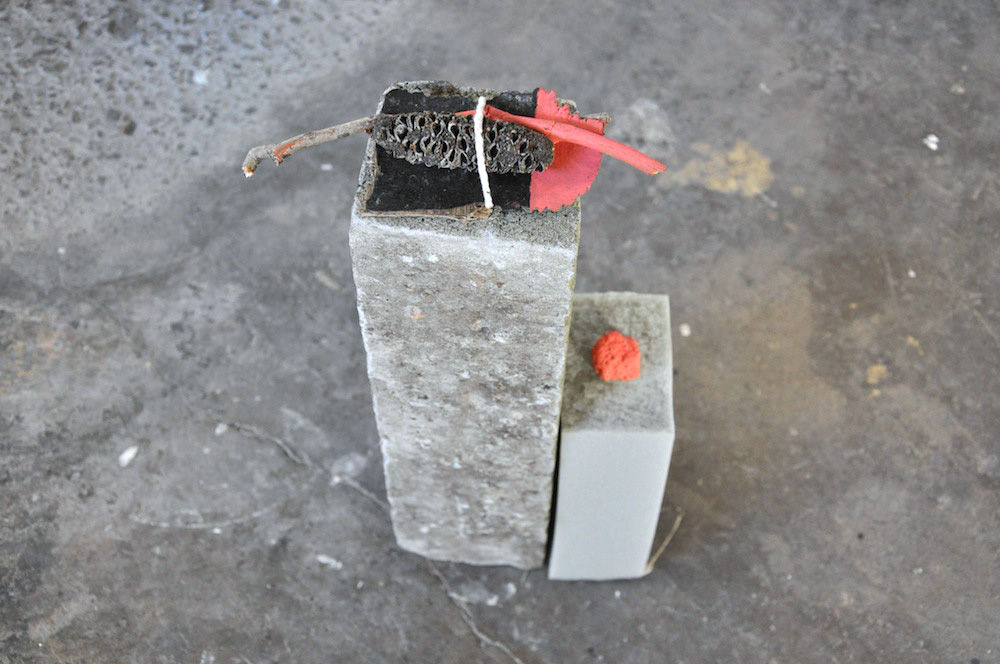

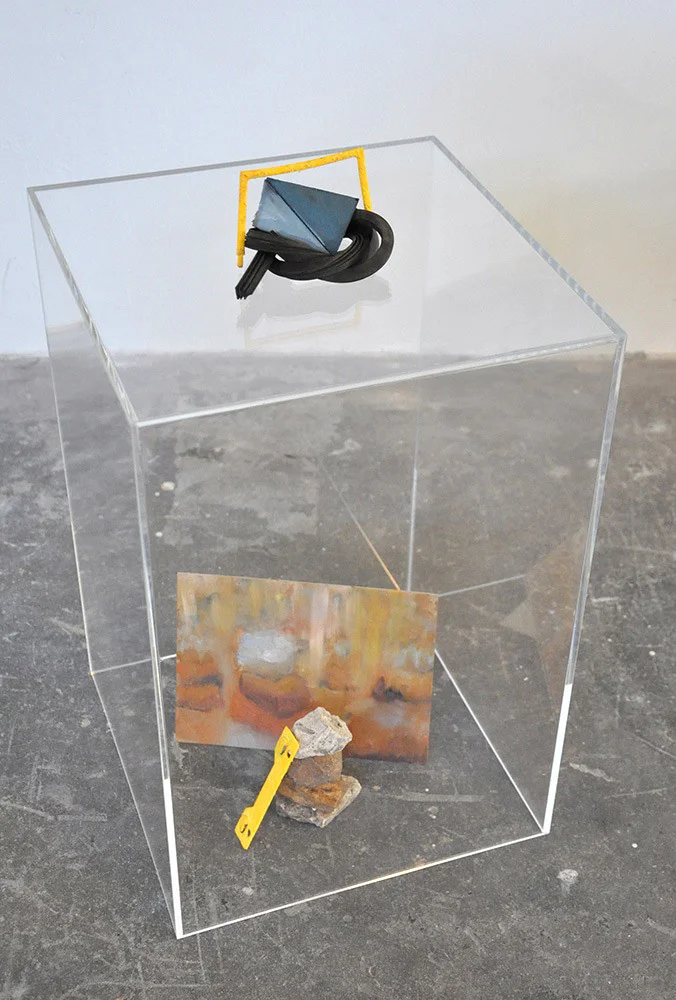

Having collected this vast array of objects, Gallo spreads out her finds in the studio. It’s this process of taking and moving objects from their original site that allows such objects to shake off their original meaning and intention. (This is all the more apparent in the pieces that have been broken or split or torn). That is to say, in the studio, objects are ascribed a new set of values—reappropriated as aesthetic objects, their use and place in the world can begin anew. They are no longer refuse, but the components of Gallo’s hanging mobile sculptures.

In reweighting and balancing these objects next to one another, Gallo is also gesturing to our personal relationship with ‘things’: how easily we assume an object doesn’t exist, just because it has disappeared from view; how uneasy it makes us when we realise such objects have a lifetime longer than our own.

Gallo approaches sculpture in the same way she approaches walking. Much like her tour of Auburn, she must show care and restraint towards her things, taking the time to match weight against weight, level against level, in order to keep everything in check. And when I look at Gallo’s mobiles, I think of the way they imply collective rather than individual action—how each object is only able to float suspended because it is tied to another, and another. It is a type of structural arrangement that runs counter to the idea of suburbia. It sits against the aggressive pursuit of a yard with a fence; it sits against closed curtains and throw-away culture; it suggests how the fragile shard of an object becomes stronger when bonded with something else.

Because what is a mobile if not the balancing of disparate individual parts, whose stable existence relies on the careful assemblage of other such parts—an offering of lives lived in tandem, rather than in opposition.

— Naomi Riddle, 2019